| |

Three-Day Weekend.

Ronald Feldman Gallery

New York

June 18 - July 29, 2005

Three-Day Weekend.

Ben Uri Gallery

The London Jewish Museum of Art

London, UK

August 7 - September 4, 2005

This show was part of the of exhibition for the winners of the 2004 Internationals Jewish Artist of the Year Award.

Vitaly Komar: Three-Day Weekend (2005). Bluebird Cafe Paintings (1967)

Matthew Bown Gallery

London, UK

August 11 - September 10, 2005

Three-Day Weekend.

Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art

The Humanities Gallery

New York

October 25 - December 11, 2005

Catalog with an introduction by Dore Ashton, Professor of Art History, Cooper Union, "The End of the End of the End of History" and an article by Andrew Weinstein, Exhibition Curator, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Art History, The Cooper Union, "The Healing Power of the Artist?" as well as an artist statement.

Vitaly Komar: Paradoxes of Collaboration in Art

Lecture/Slide-Performace

Guggenheim Museum

New York

December 6, 2005

In conjunction with the group show "Russia!"

Vitaly Komar: Paradoxes of Collaboration in Art

Lecture/Slide-Performace

Ahmatova Museum

St. Petersburg, Russia

June 14, 2006

Vitaly Komar: Paradoxes of Collaboration in Art

Lecture/Slide-Performace

State Center of Contemporary Art

Moscow, Russia

June 19, 2006

Russian Sots Art and American Pop Art

Lecture/Slide-Performace

Mayakovsky Public Library

St. Petersburg, Russia

June 15, 2006

Russian Artist in the West

Lecture/Slide-Performace

The State Tretikov Gallery

Moscow, Russia

June 20, 2006

Selected Publications:

Pinakotheke, No. 22-23. 2006/1-2. "Where is the Line Between Us? Interview with Vitaly Komar" by Julia Tulovsky.

Hermitage #4, 2006. My Hermitage, by V. Komar (pp. 80).

Boulevard, Vol. 21, No 2 & 3, Spring 2006. Published by Saint Louis University. "Irony and Mystery: Vitaly Komar’s Three-Day Weekend", by Andrew Weinstein (pp. 116-122).

Gorod (The City, in Russian), Aug. 21, 2006. Interview with V. Komar, by Elena Nekrasova.

Studies in Slavic Cultures IV, Center for Russian and European Studies, University of Pitsburg, 2006. Cover Art.

Reviews of Three-Day Weekend.

Nick Stillman, "Vitaly Komar", ArtForum.com, 2005.

"Vitaly Komar", The New Yorker, July 11 & 18, 2005.

Ken Johnson, "Vitaly Komar Three-Day Weekend", The New York Times, July 1, 2005.

"Three-Day Weekend", Jewish Renaissance Quarterly, Vol 4, Issue 4, July 2005.

Amoreen Armetta, "Vitaly Komar", Flash Art 75, October 2005.

Haim Mendelev, "Vitaly Komar: Three-Day Weekend", Russian Forward, #501, July 1-7, 2005.

Martin Coomer, "Vitaly Komar", Time Out London, 57, August 24-31, 2005.

JL, "Vitaly Komar", The Guardian, The Guide, August 27 - September 2, 2005.

Robert Baker, "Voice Pick, Vitaly Komar", Village Voice, November 16-22, 2005.

Edward Leffingwell, "Vitaly Komar at Ronald Feldman", Art in America, no. 11, December 2005.

VITALY KOMAR

Three-Day Weekend

Artist Statement

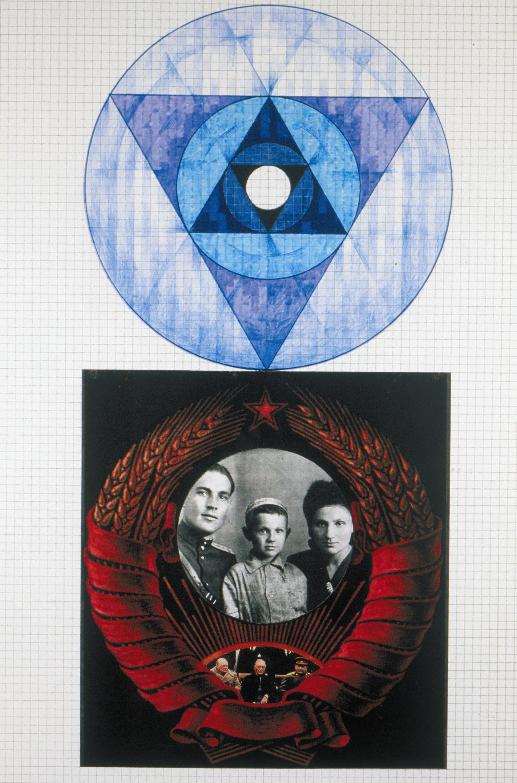

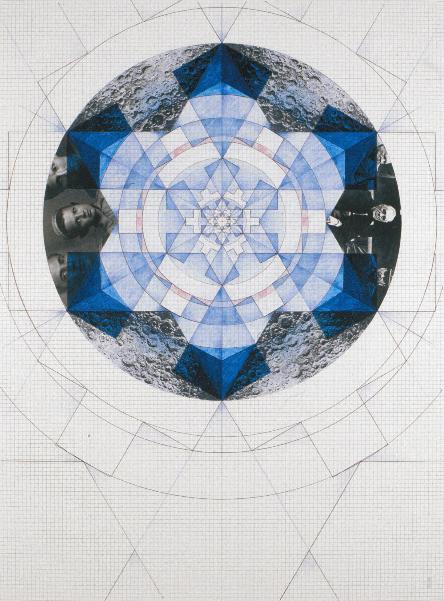

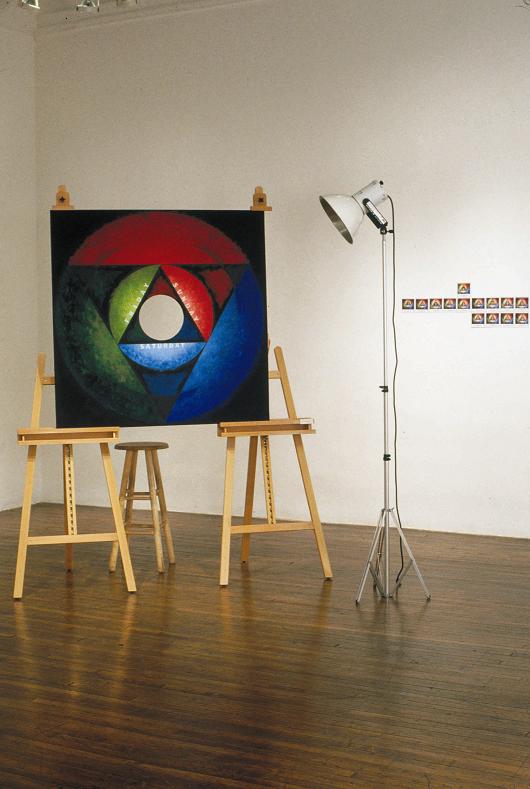

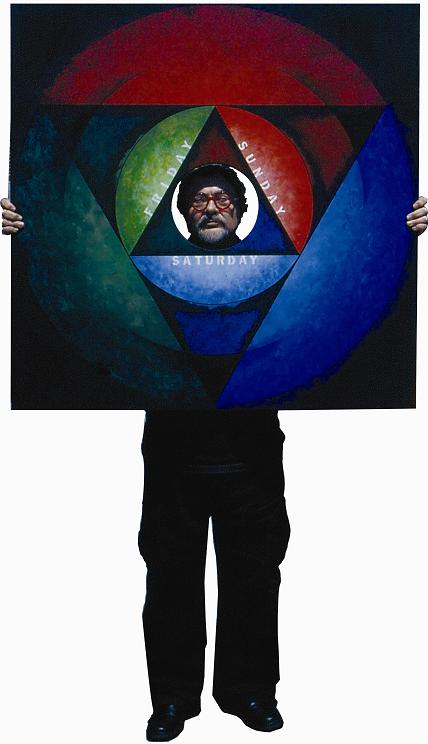

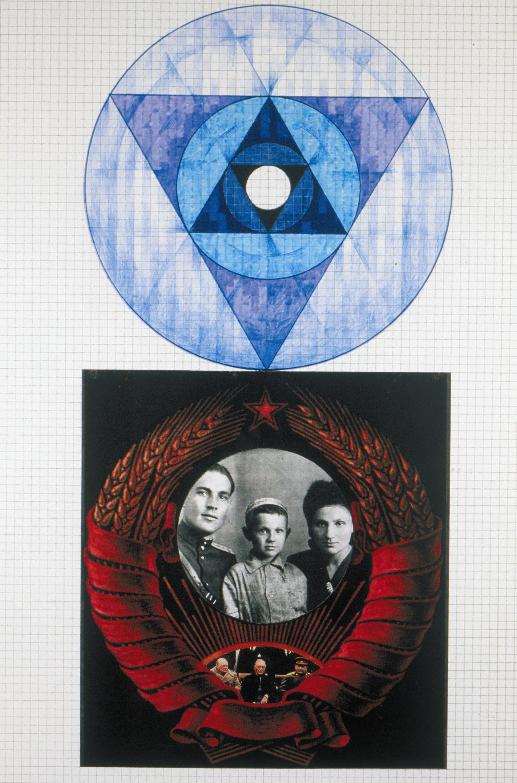

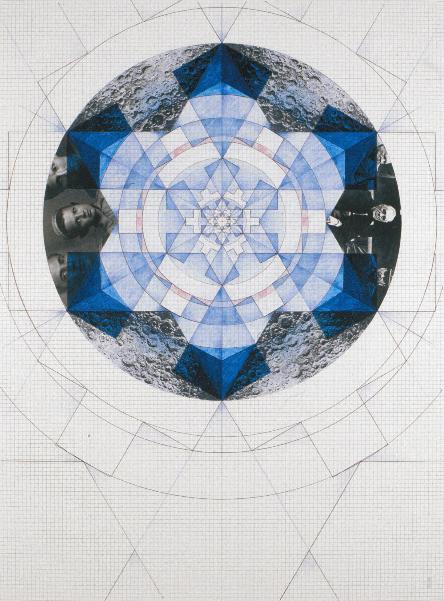

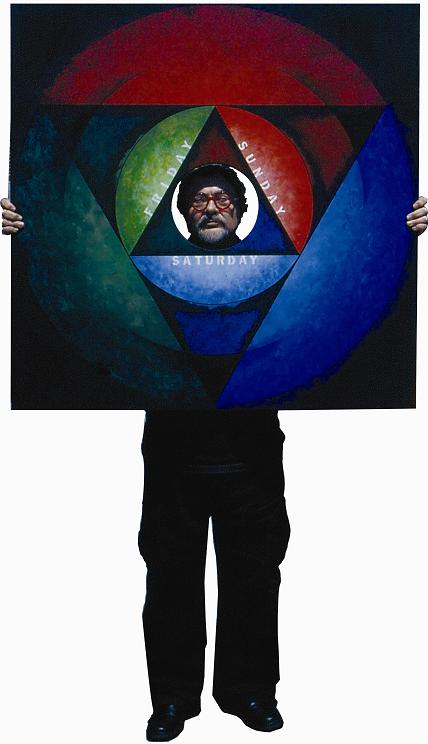

The Three-Day Weekend, for me, is a symbol of the peaceful coexistence of different peoples and different concepts of faith and spirituality: Friday for Muslims, Saturday for Jews, and Sunday for Christians. The idea to create ecumenical symbols in the form of Universal Mandalas originated in childhood dreams. It continues the search of the nonconformist art of my youth. In these mandalas, I unite ancient symbols of spirituality with historical and personal images.

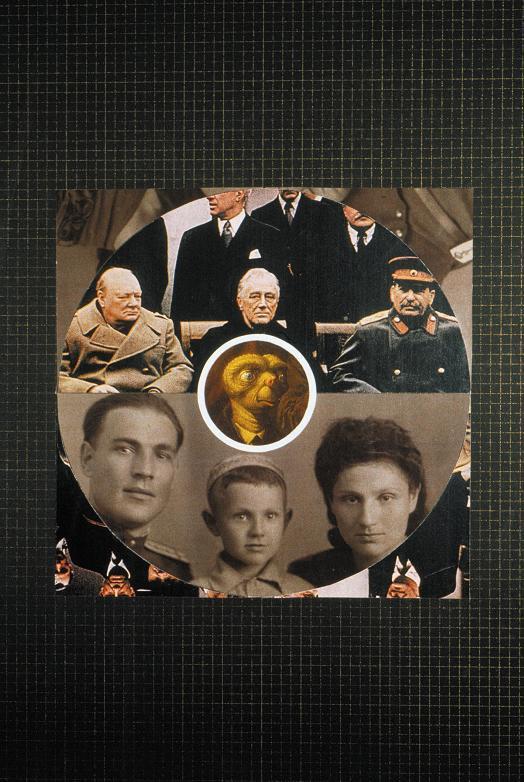

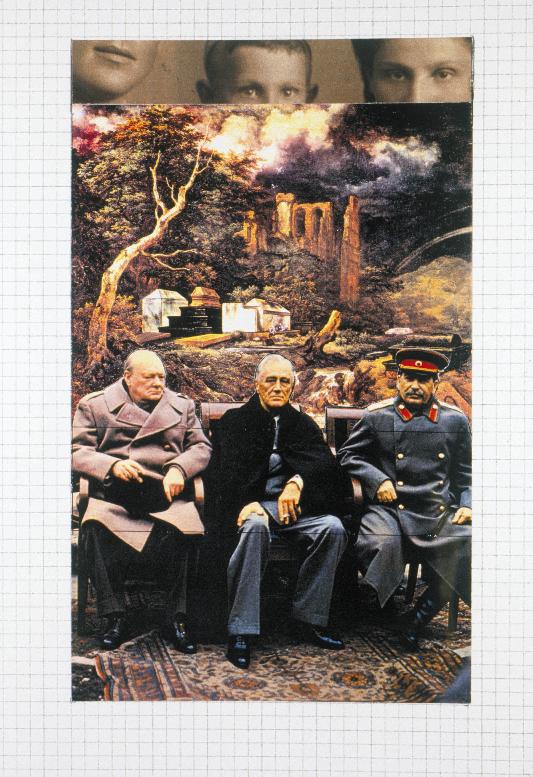

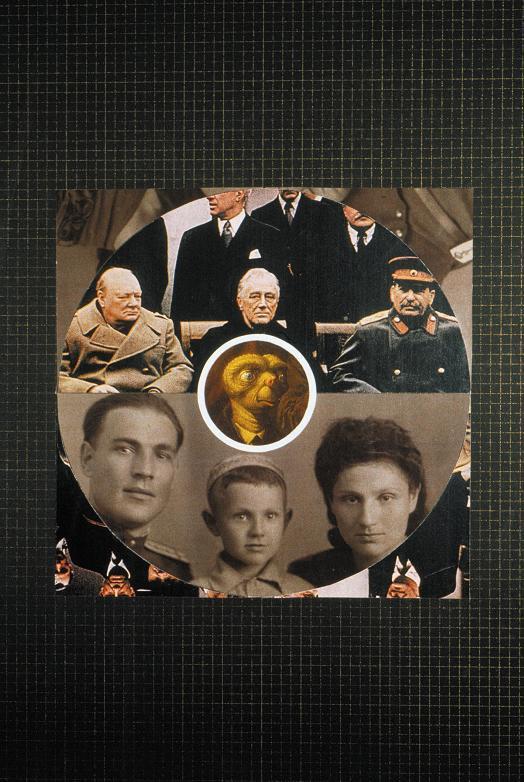

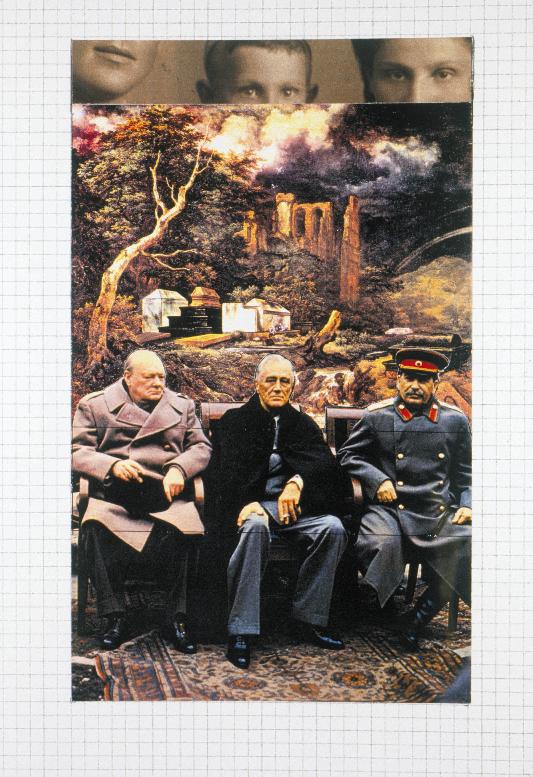

My imagination unites images and concepts that are distant and seemingly opposite. I first saw a picture of the Yalta Conference, an image that was banned in the Soviet Union, in the 1980s in New York. Afterwards, for many years I could not understand why I was so haunted by it. Back then, I made several paintings on this theme. In the first, I transformed Roosevelt’s face into the face of ET – a child and alien in America who is from another planet and possibly a different political system.

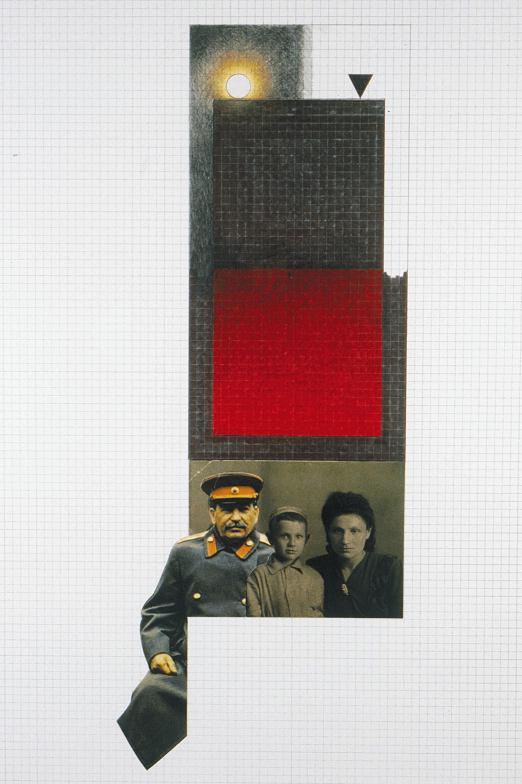

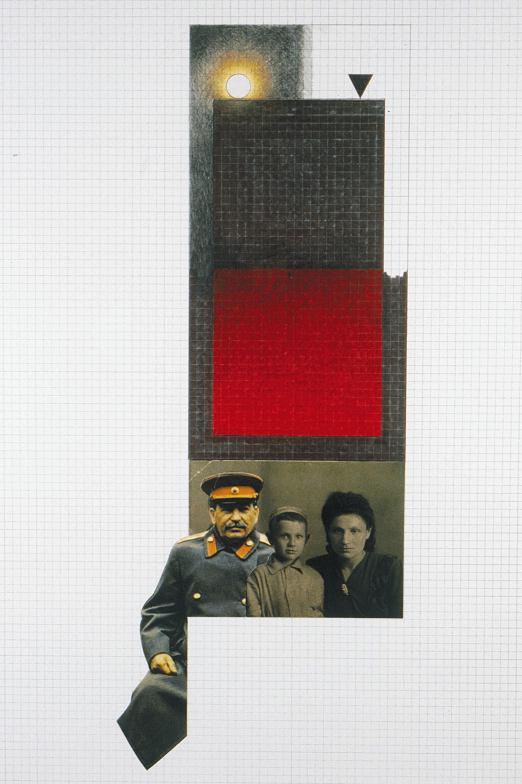

Two years ago, while looking through old family photographs, I rediscovered a portrait of me with my mother and father that was my favorite in childhood but which I have long since forgotten. My father is dressed in his military uniform. It was taken shortly after the end the Second World War, and it was the last time that the three of us were together. I was six, my parents would soon be divorced, and my father would shortly leave Moscow. I never saw him again.

When I saw this portrait, I suddenly thought about the image of Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. Placing these two photographs side by side, I realized that the picture of Yalta had haunted me because unconsciously I saw in it a forgotten picture of my family. In the depths of my memory, these two trinities had become superimposed. I understood also that the image of ET in my old painting was a self-portrait; it was me – a Russian Jew, an alien from a different world.

The main reason for my parents’ divorce was that the Jewish traditions of my mother’s family could not coexist peacefully with my father’s Christian ones. For me, these two photographs became a symbol of a fragile unity— the unity of the Allies just before the Cold War, and of my family not long before my parents’ divorce. An old, naïve dream of a happy family, of peaceful coexistence between peoples, ethnic groups and religions, came back to me through these pictures.

During my Soviet childhood, a weekend lasted only one day – Sunday. This caused a great deal of hardship for my Jewish grandparents, who had difficultly obtaining permission to move their free day from Sunday to Saturday. After Stalin’s death, the government instituted a two-day weekend. I was a teenager then, but even now, the two-day weekend – Saturday and Sunday – seems to me a symbol of the peaceful coexistence of Judaism and Christianity. Wouldn’t it be great, I thought, to add one more flower to this bouquet – Friday – to include Abdul, my Tartar classmate, whose Muslim family lived in our building?

These visions and dreams were typical of our small circle of nonconformist artists, the friends of my youth. We would drink, recite poetry, and talk about Sots Art (Soviet pop/conceptual art) and dukhovka (spiritual questions) until sunrise. Sots Art was a kind of ironical iconoclasm, whereas dukhovka, a slang expression of Moscow’s bohemia, expressed a dream of an ecumenical mysticism. I’ve always loved Gogol’s cocktail of irony and mysticism. In the beginning of the 1970s, in a multi-stylistic installation called Paradise, Alex Melamid and I tried to combine Sots Art and dukhovka in one, synthetic work. I dreamed of making symbols that united heraldry and mandalas, irony and spirituality, symbols that would genuinely represent the peaceful coexistence of peoples and religions, something that the state emblems—the hammer and sickle, the various state eagles—did not actually accomplish. Unfortunately, Paradise, which was housed in my father-in-law’s apartment, was dismantled on the orders of state authorities.

We were constantly surrounded by Soviet pop culture—state-sponsored official art and visual propaganda. Publications, exhibitions, and sales of art were controlled by the Soviet government. Under these circumstances, pursuing money and fame meant selling your soul to the devil. Out of principle, many of us chose to make our living as something other than artists. We made art “for the soul,” during free time on weekends. The two days seemed so short that I dreamed of having at least one more “creative day.” My utopia of the three-day weekend was dangerous. This idea could have united people more effectively than Marxism. The idea of the peaceful coexistence of different ideologies was viewed by the government as anti-Soviet propaganda. The common enemy of totalitarian atheistic fundamentalism united us with various dissident groups. I think that Hitler, the common enemy, united the superstars of the Yalta conference in a similar way. In the future, friends, not enemies, must bring us together.

The search for spirituality in art, begun by Kandinsky during the flowering of the Russian avant-garde, was interrupted first by Stalin, and later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, by the advent of the capitalist free market. I never imagined that my artist friends and I would be transformed from the so-called avant-garde of spiritual and intellectual life to the avant-garde of real estate. At the beginning of the 21st century, both in Russia and in the West, we have gained much, but have forgotten much too, just as I had forgotten my childhood photograph.

Nostalgia for the nonconformist art of my youth made me return to its unfulfilled dreams and experiments. The painting of ET was part of the Nostalgic Socialist Realism series, made with my old friend Alex. But when I began uniting symbols of spirituality with childhood photographs of me and my parents, I embarked on a deeply personal work. Today, I understand the concept of artistic collaboration very broadly. I continue to collaborate with art history, with the nonconformist art of my youth.

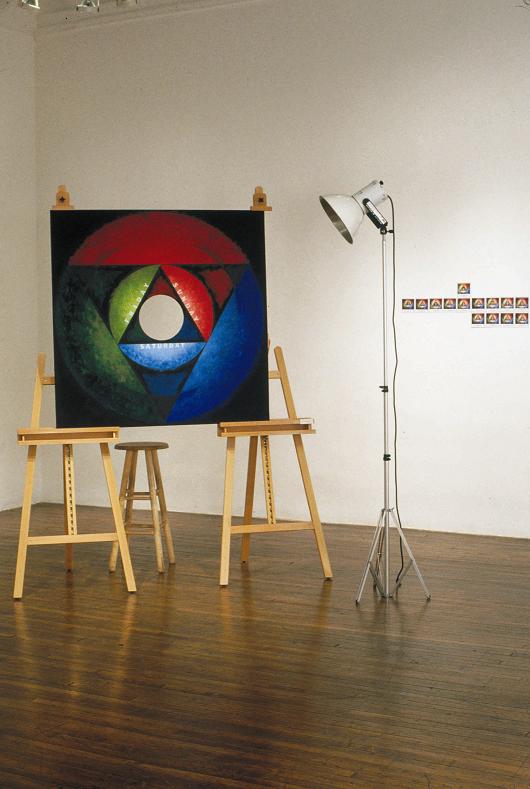

At some point during work on these photographs, a face—mine or one of the others—appeared in the center of some of the mandalas. These accidents gave me the idea of making painted and stained glass panels with a hole or a mirror in the center of the mandala. Visitors who’d like to participate in this project can place their faces in the opening of certain mandalas, or see their reflection in the mirror in the others. I will photograph them with a Polaroid camera and make ID-like, pocket-sized mandala portraits. In this way, spectators can establish a personal connection with eternal symbols of spirituality and the concept of the Three-Day Weekend. I invite everybody to make an appointment.

The exhibition and publication of these symbols will be the initial step in the creation and promotion of a not-for-profit Three-Day Weekend Society.

VITALY KOMAR

Three-Day Weekend

Brief Description of Project.

The Three-Day Weekend , for me, is a symbol of the peaceful coexistence of different peoples and different concepts of faith and spirituality: Friday for Muslims, Saturday for Jews, and Sunday for Christians.

The idea to create ecumenical symbols in the form of Universal Mandalas originated in my childhood dreams, and continues the search of the nonconformist art of my youth. In these mandalas, I unite ancient symbols of spirituality with historical and personal images (see Artist’s Statement).

At some point during my work with photographs of me and my parents, a face—mine or one of the others—appeared in the center of some of the mandalas. These accidents gave me the idea of making painted and stained glass panels with a hole or a mirror in the center of the mandala. Visitors who’d like to participate in this project can place their faces in the opening of certain mandalas, or see their reflection in the mirror in the others. I will photograph them with a Polaroid camera and make ID-like, pocket-sized mandala portraits. In this way, spectators can establish a personal connection with eternal symbols of spirituality and the concept of the Three-Day Weekend. I invite everybody to make an appointment.

The exhibition and publication of these symbols will be the initial step in the creation and promotion of a not-for-profit Three-Day Weekend Society.

Vitaly Komar: Brief Biography

Vitaly Komar was born in Moscow, USSR in 1943, graduated from the Stroganov School of Art and Design in 1967, and has been living in New York since 1978. He was one of the founders of the Sots Art movement (soviet Pop/Conceptual art) and a pioneer of multi-stylistic post-modernism (1972-73).

Vitaly Komar worked in collaboration with Alex Melamid from 1973 to 2003. In 1974, he was arrested during a performance of Art Belongs to the People and later, on September 15th, his and A. Melamid’s work along with the works of other non-conformist artists was destroyed by Soviet Authorities at the open-air Bulldozer Exhibition.

Komar and Melamid can be found in Oxford’s Dictionary of 20th Century Art; The Penguin Concise Dictionary of Art History; Art since the 40’s; Bildende Kunst im 20 Jahrhundert; Bordas’ Petit Dictionnaire Des Artistes Contemporains; Art in the Modern Era; and Phaidon’s The 20th-Century Art Book. Their work is included in major art museums across the world.

They collaborated with the conceptual video artist Douglas Davis on Questions New York/Moscow in 1976 (collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); with Fluxus musician Charlotte Moorman on Passport in 1976 (Ronald Feldman Gallery); with Pop Artist Andy Warhol on We Buy and Sell Souls in 1978-79 (private collection, Moscow); with dozens of artists and Soviet monuments on Monumental Propaganda in 1993 (traveling show, Independent Curators Inc.); with the masses and Marttila & Kiley Poll Company on Most Wanted and Most Unwanted Paintings in 1994; with composer Dave Soldier on an opera about Washington, Lenin and Duchamp, Naked Revolution in 1997 (Walker Art Center, Minneapolis and The Kitchen, New York);with painter Renee the elephant in 1995 and with photographer Mikki the Chimpanzee in 1998 (Russian pavilion at Venice Biennale, 1999).

After the Symbols of the Big Bang (quest for spirituality in science and natural forces) exhibited at the Yeshiva University Museum (New York, 2002-03) the artist started the Three-Day Weekend uniting symbols of different faiths and concepts of spirituality with childhood photographs of him and his parents. This deeply personal work marked the end of his collaboration with Alex Melamid, but the artist understands the concept of artistic collaboration very broadly. “I continue collaborating with art history” said Vitaly Komar, “with the nonconformist art of my youth and its unfulfilled dreams and experiments.”

Works From the Three-Day Weekend Project

|

|

| Fragile Unity with E.T. |

Between Darkness and Light |

|

|

| Yalta Conference at a Jewish Cemetery |

Mandala Above State Heraldry #1 |

|

|

| Four Moons as Part of a Snowflake |

Three-Day Weekend Stained Glass with Mirror |

|

|

| Mandala for Photographs #1 |

Vitaly Komar |

|